GUARD Protocol: Gastric Ultrasound for Aspiration Risk Determination

by Allyson Hansen, D.O. & Charlotte Derr, MD, RDMS, FACEP

Imagine you’re working in a solo community shop!

A 45-year-old female comes to the ED with a left shoulder deformity and severe pain after speeding through downtown Tampa on an electric scooter for which she lost control. Unfortunately, she crashed into the sidewalk onto her left shoulder. X-ray displays a shoulder dislocation, just as you suspected!

The patient says she has HTN, HLD and you note a BMI of 40. She was recently started on Ozempic, a GLP-1receptor agonist. As usual, you think of the various offerings to assist with reduction: nerve block, intra-articular injection or moderate sedation? Hmmm…You perform a focused airway assessment recalling the LEMON mnemonic and determine her airway is predicted to be difficult.

Should you be considering any more investigation before deciding on analgesia and anesthesia and attempting shoulder reduction?

What We Know

GLP-1 receptor agonists have increased in use particularly in the bariatric and weight loss world! More and more of our patients are on these medications, but not only for diabetes. These medications have shown to have weight loss effects through varying mechanisms. One important effect of this medication is delayed gastric emptying which in the early administration of long acting injectables, is quite profound but seems to improve after 12-20 weeks of use (1). This may not be true in the short acting, once daily oral medications (2).

Recently there has also been alarm in the anesthesiology community as small studies have been published associating use of GLP-1 receptor agonists with high residual gastric volumes in those reported as fasting as well as case studies showing aspiration occurrences in this population during anesthesia (2,3,4,5,6,7).

So, what can be done to assess these patients prior to anesthesia and analgesia?

Enter gastric ultrasound (US)! Gastric US has shown to be a reliable predictor of gastric volume assessment preoperatively and it is easy to perform (8,9,10, 11, 12, 13, 14).

Gastric US is as easy as 3 steps!

Patient supine first. Place probe in epigastric region using the curvilinear abdominal probe if performing on average sized adult. You will be in the sagittal plane with the probe indicator pointed towards the patient’s head (Image 1). Look for the left liver lobe and aorta. Your goal is to find the gastric antrum, which has shown to be a reliable surrogate for gastric content volume. The antrum will appear between the liver and aorta. You can appreciate the wall’s “gut signature” or multi-layered appearance. In Video 1, note the gastric antrum wall layers are more noticeable in an empty stomach. The hyperechoic center is the bright mucosal walls juxtaposed. You will want to note if the antrum is empty, has anechoic/dark fluid with a few bright bubbles or if it is complex with echogenic material.

Image 1 (left). Location of probe in supine patient. Probe indicator towards the head, sagittal plane at epigastrium.

Video 1 (above): Clip of gastric antrum. Note the liver in the left (cephalad) screen and the long axis of the aorta in the farfield. Between these two structures lies the gastric antrum with a layered (sometimes referred to as a “bulls eye”)appearance. The bright echogenic mucosal walls are juxtaposed as this is an example of an empty gastric antrum.

2. Then, you will want to roll your patient to the right lateral decubitus position (RLD) (Image 2). This allowsany hidden gastric contents to move to the gastric antrum or the most dependent position of the stomach. You roll your patient and note the gastric antrum is no longer empty in appearance but there is anechoic fluid (Video 2).

Is this more than regular gastric secretions?

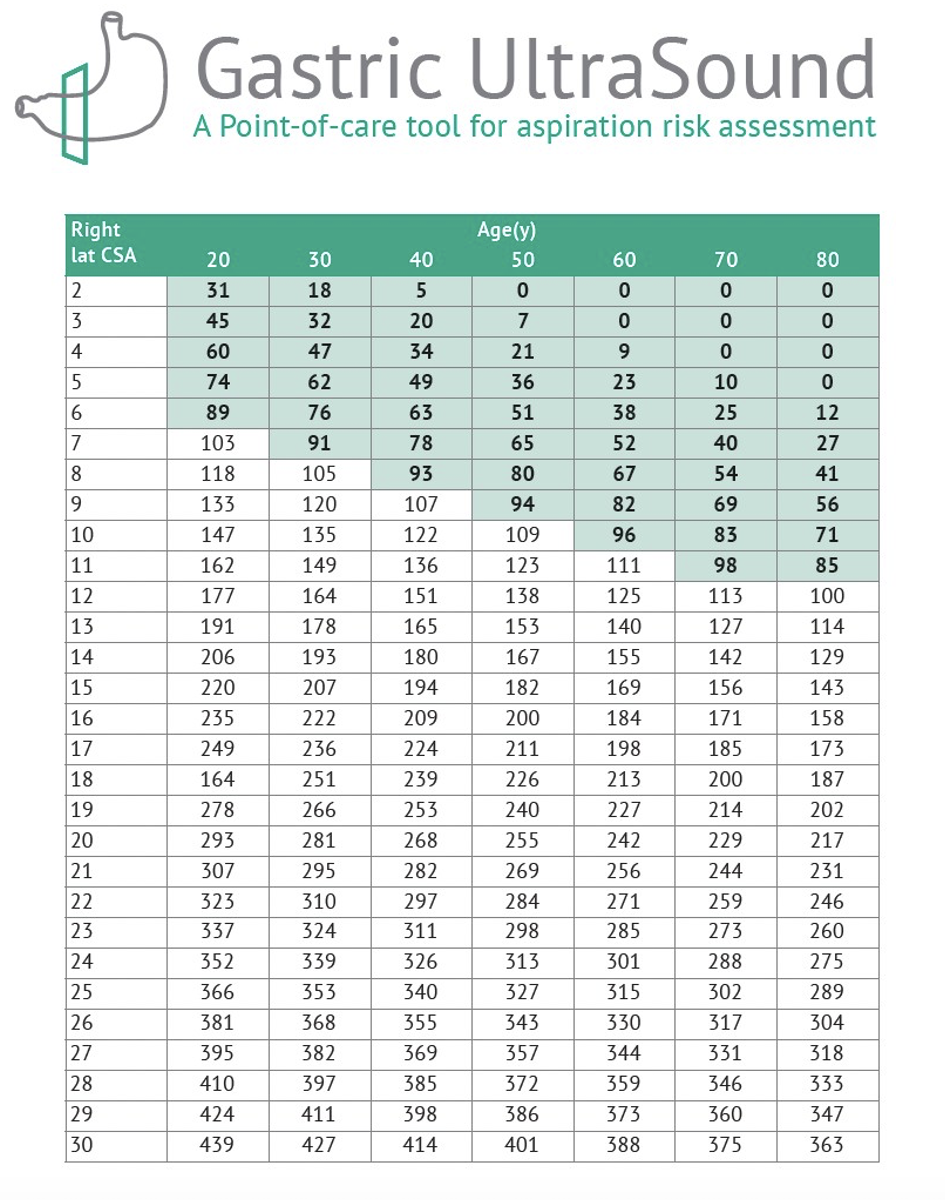

You must measure the cross-sectional area of the gastric antrum (CSA) on your ultrasound machine (Image3) and use this as well as patient age to estimate the predicted gastric volume to determine if the gastric contents is more than normal gastric secretions. Luckily, Perlas et al. has a validated chart to do this! (Table 1).

Image 2 (above). Right lateral decubitus position with probe in epigastrium, sagittal plane.

Video 2 (left). Clip of a gastric antrum with anechoic fluid.

Image 3. RLD image of the gastric antrum CSA. RLD= right lateral decubitus, CSA= cross sectional area.

Figure 1. Gastric volume assessment using CSA and age. Created by: gastricultrasound.org

3. Estimate the volume for anechoic gastric contents only. If the number falls into the shaded region of Figure 1, yourpatient is considered low risk for aspiration! Conversely, if you see any complex fluid such as hazy, dirtyshadowing or a “frosted glass” appearance this is considered a “full” stomach and at elevated risk foraspiration. No need to measure. Note the difference between “empty”, “fluid” and a “full” gastric antrum in Image 4.

Image 5. Complex or “full” gastric antrum. This appearance is considered at elevated risk for aspiration duringsedation and no CSA needs to be performed to further risk stratify.

CSA= cross-sectional area.

Image 4. Full vs. Fluid vs. Empty. The “full” gastric antrum may have a “frosted glass” or dirty shadow appearance.Early in consumption of food and fluids, you may have more echogenic air bubbles. It is challenging to see thelayered walls of the antrum with a full stomach. If any simple appearing “fluid is identified, a CSA should bemeasured. The “empty” antrum has identifiable layered walls and a mucosal surface juxtaposed and hyperchoic. CSA= cross-sectional area.

Pulmonary Aspiration & Sedation

Should I care? Do GLP-1 receptor agonists increase the risk of aspiration during moderate sedation in the ED?

The answer is YES you should care. Aspiration has a high mortality and morbidity. These medications mayincrease the risk of aspiration. We still need more data from ED performed procedural sedations, specifically in this patient population.

Note the risk of aspiration in the general population is a relatively rare event with the estimated rate of pulmonary aspiration during anesthesia to be 1:350,000 in adults and 9:10,000 in pediatrics (15). The overall incidence inaspiration during anesthesia performed moderate sedation has shown to be roughly 1:3400 with mortality1:125,000 (16). Also note, ASA guidelines on fasting times are largely based on consensus agreement (17). The ASArecognizes that the currently available literature may not provide sufficient evidence, but ASA’s position remains conservative.

Can we extrapolate this data from the OR to the ED?

Not necessarily. We have a different patient population, we perform procedural sedation with little airway manipulation (when most aspiration occurs), we do not use inhaled anesthetics known to be emetogenic, and ourhigh utilization of ketamine tends to preserve airway reflexes(16).

There is a paucity of literature on the rate of aspiration during ED performed procedural sedation. According to theACEP Policy on Procedural Sedation, last updated in 2018, no literature has shown a significant risk of emesis oraspiration during procedural sedation when compared to fasting times.

ACEP Clinical Policy Procedural Sedation and Analgesia states (18):

“Do not delay procedural sedation in adults or pediatrics in the ED based on fasting time. Pre-proceduralfasting for any duration has not demonstrated a reduction in the risk of emesis or aspiration when administering procedural sedation and analgesia.”

Level B Recommendation. This is based on 5 trials and only one including adults (19).

Considering these recommendations, the rapidity in growth and utilization of GLP-1 receptor agonists and datalacking in terms of pulmonary aspiration in this population taking these meds, should we be revisiting pre-procedural sedation evaluations and focusing our efforts on this population?

Implications for Emergency Physicians

Although there is a paucity of literature surrounding the incidence of aspiration during emergency airwayprocedures and moderate sedation, we believe prophylactic safety measures should be undertaken whileresearch is being done. The continued utilization of risk stratification tools as well as considering the addition ofgastric US for the population on GLP-1 receptor agonists (who can often be high risk for aspiration or difficultairways) is something to keep in your back pocket at the bedside.

We have started a patient safety initiative and are performing gastric US. The “GUARD Protocol” has been used inthe endo-suite and in the ED to assess GLP-1 receptor agonist patient’s risks for aspiration during moderate sedation. Stay tuned for results!

Take a look at “Hot Tip - GUARD Protocol” for a great reminder how to perform this exam/protocol. Also download the Quick TipSheet, tag it for fast bedside recall. These plus more, can be found at the QR code below:

Denouement

You decide to perform a gastric US on your patient. Supine, your patient has no visible content and in RLD younote anechoic fluid so decide to measure the CSA to see if the volume is suggestive of more than just normalgastric secretions. Since there has been well validated anesthesia literature correlating gastric antrum CSA andage with volume, you plot this and realize the patient has little gastric content and is at low risk for aspiration. Youexplain to her the options and she is adamant on “being put out!” You proceed with moderate sedation for the procedure.

References

Silveira SQ, da Silva LM, de Campos Vieira Abib A, de Moura DTH, de Moura EGH, Santos LB, Ho AM, Nersessian RSF, Lima FLM, Silva MV, Mizubuti GB. Relationship between perioperative semaglutide use and residual gastric content: A retrospective analysis of patients undergoing elective upper endoscopy. J Clin Anesth. 2023 Aug;87:111091. PMID: 36870274.

Nauck MA, Quast DR, Wefers J, Meier JJ. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes - state-of-the-art. Mol Metab. 2021 Apr;46:101102. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101102. Epub 2020 Oct 14. PMID: 33068776; PMCID: PMC8085572.

Klein SR, Hobai IA. Semaglutide, delayed gastric emptying, and intraoperative pulmonary aspiration: a case report. Can J Anaesth. 2023 Aug;70(8):1394-1396. English. doi: 10.1007/s12630-023-02440-3. Epub 2023 Mar 28. PMID: 36977934.

Klein SR, Hobai IA. Semaglutide, delayed gastric emptying, and intraoperative pulmonary aspiration: a case report. Can J Anaesth. 2023 Aug;70(8):1394-1396. PMID: 36977934.

Jones PM, Hobai IA, Murphy PM. Anesthesia and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: proceed with caution! Can J Anaesth. 2023 Aug;70(8):1281-1286. PMID: 37466910.

Gulak MA, Murphy P. Regurgitation under anesthesia in a fasted patient prescribed semaglutide for weight loss: a case report. Can J Anaesth. 2023 Aug;70(8):1397-1400. PMID: 37280458.

Sherwin M, Hamburger J, Katz D, DeMaria S Jr. Influence of semaglutide use on the presence of residual gastric solids on gastric ultrasound: a prospective observational study in volunteers without obesity recently started on semaglutide. Can J Anaesth. 2023 Aug;70(8):1300-1306. PMID: 37466909.

Perlas A, Chan VW, Lupu CM, Mitsakakis N, Hanbidge A. Ultrasound assessment of gastric content and volume. Anesthesiology. 2009 Jul;111(1):82-9. doi: 10.1097/ ALN.0b013e3181a97250. PMID: 19512861.

Perlas A, Davis L, Khan M, Mitsakakis N, Chan VW. Gastric sonography in the fasted surgical patient: a prospective descriptive study. Anesth Analg. 2011 Jul;113(1):93-7. doi: 10.1213/ ANE.0b013e31821b98c0. Epub 2011 May 19. PMID: 21596885.

Kruisselbrink R, Arzola C, Jackson T, Okrainec A, Chan V, Perlas A. Ultrasound assessment of gastric volume in severely obese individuals: a validation study. Br JAnaesth. 2017 Jan;118(1):77-82. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew400. PMID: 28039244.

Moake MM, Presley BC, Hill JG, Wolf BJ, Kane ID, Busch CE, Jackson BF. Point-of-Care Ultrasound to Assess Gastric Content in Pediatric Emergency Department Procedural Sedation Patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022 Jan 1;38(1):e178-e186. PMID: 32769837; PMCID: PMC7854775.

Bouvet L, Miquel A, Chassard D, Boselli E, Allaouchiche B, Benhamou D. Could a single standardized ultrasonographic measurement of antral area be of interest for assessing gastric contents? A preliminary report. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009 Dec;26(12):1015-9. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32833161fd. PMID: 19707146.

Van de Putte P, Perlas A. Ultrasound assessment of gastric content and volume. Br JAnaesth. 2014 Jul;113(1):12-22. doi: 10.1093/bja/ aeu151. Epub 2014 Jun 3. PMID: 24893784.

Ricci R, Bontempo I, Corazziari E, La Bella A, Torsoli A. Real time ultrasonography of the gastric antrum. Gut. 1993 Feb;34(2):173-6. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.2.173. PMID: 8432467; PMCID: PMC1373964.

Cook TM, Woodall N, Frerk C; Fourth National Audit Project. Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 1: anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2011 May;106(5):617-31. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer058. Epub 2011 Mar 29. PMID: 21447488.

Green SM, Krauss B. Pulmonary aspiration risk during emergency department procedural sedation--an examination of the role of fasting and sedation depth. Acad Emerg Med. 2002 Jan;9(1):35-42. doi: 10.1197/aemj.9.1.35. PMID: 11772667

Practice Guidelines for Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration: Application to Healthy Patients Undergoing Elective Procedures: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preoperative Fasting and the Use of PharmacologicAgents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration. Anesthesiology. 2017 Mar;126(3):376-393. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001452. PMID: 28045707.

Godwin SA, Burton JH, Gerardo CJ, Hatten BW, Mace SE, Silvers SM, Fesmire FM; American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2014 Feb;63(2):247-58.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.10.015. Erratum in: Ann Emerg Med. 2017 Nov;70(5):758. PMID: 24438649.

Bell A, Treston G, McNabb C, Monypenny K, Cardwell R. Profiling adverse respiratory events and vomiting when using propofol for emergency department procedural sedation. Emerg Med Australas. 2007 Oct;19(5):405-10. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.00982.x. PMID: 17919212.

About the Authors

Dr. Hansen is the Ultrasound Director at the University of South Florida Emergency Medicine Program. Dr. Derr is the Ultrasound Fellowship Director and the Residency Director for the University of South Florida Emergency Medicine Residency Program.