Balloon Tamponade in GI Bleed

by Michael Simoes, M.D.

Background

About 50% of patients with cirrhosis have gastroesophageal varices, and the presence of them is associated with severity of liver disease. The Child-Pugh scoring system is often used to predict mortality. For example, Child’s B and C cirrhosis will have a greater rate of variceal hemorrhage, recurrent bleeding, larger varices, and higher risk of failure to control bleeding. While there have been significant advancements in management of cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and prevention of variceal bleeding, there are times in which temporizing measures must be used in the emergency department when conventional treatments are not enough.

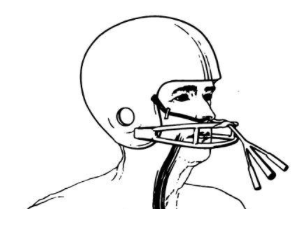

In the 1950s, the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube (SBT) was conceptualized by Robert William Sengstaken Sr. (an American neurosurgeon) and Arthur Blakemore (an American vascular surgeon). This balloon tamponade device has both gastric and esophageal balloons with 3 ports: gastric inflation, esophageal inflation, and gastric suction. Later on, the Minnesota tube was invented with a similar design to the SBT, but has the addition of a fourth port that allows for esophageal suction as well. There is also the lesser-known Linton-Nachlas tube that only has a gastric balloon and 2-3 ports.

The use of a balloon tamponade device such as the SBT or Minnesota tube is indicated when there is uncontrolled hemorrhage from gastric and/or esophageal variceal bleeding after medical or endoscopic treatment fails or is not available. They are contraindicated if the patient has an unprotected airway, an esophageal rupture, esophageal stricture, the source of bleeding is not gastric or esophageal, or if the variceal bleeding is already well controlled.

What equipment do I need?

SBT or Minnesota Tube

Large syringe (50cc)

Basin of water

Kelly clamps with tape

3-way stopcocks

Lubricant jelly

Kerlix bandage roll

1L bag of fluid or 2lb weight

IV pole

Manometer

Process of placement

Typically, the patient is endotracheally intubated first for airway protection, and should be supine with head of bed elevated 45 degrees. Once you’ve gathered all necessary materials for the procedure, it is important to ensure there are no leaks in the balloons. Submerge the tube in the basin of water and inflate the gastric and esophageal balloons looking for any bubbles or air leaks. Next, evaluate the compliance of the gastric balloon (SBT ~250-300cc vs Minnesota ~450-500cc). Once you’ve confirmed there are no leaks and the balloons have adequate compliance for the required volume, deflate the balloons. Then, estimate the length of tube by bridge of the nose to the xiphoid process (roughly 50cm). Thoroughly lubricate the tube and balloons. The tube can be inserted nasally or orally; however, it is helpful to use laryngoscopy in order to visualize the tube going into the esophagus. Once the tube has reached the point estimated to be in the stomach, inflate the gastric balloon with 50cc of air. Confirm proper position with chest x-ray.

Once you are confident the gastric balloon is passed the esophageal sphincter and in the stomach, you may inflate the gastric balloon with 50cc increments up to 250-300cc for SBT or 450-500cc for Minnesota. Next, apply traction to the tube by tying one end of a kerlix bandage roll to the end of the tube and the other end of the roll to a 1L bag of fluids, and hang the bandage with weight on an IV pole. This will allow 1kg of traction to the tube, keeping the gastric balloon against the fundus.

At this time, a nasogastric tube may be inserted to aspirate any blood from the esophageal space if using SBT, or utilize the esophageal suction port if using Minnesota. If there is continued bleeding, the esophageal balloon will need to be inflated for further tamponade. When inflating the esophageal balloon, one must achieve a desired pressure rather than volume. The esophageal balloon should be inflated to a pressure of 30 mmHg. By utilizing a manual sphygmomanometer and a 3-way stopcock you can titrate the amount of air needed to reach 30 mmHg. If at that time, bleeding persists you may increase to a maximum of 45 mmHg. Continue to manage the patient following standards of care, likely involving GI consult for endoscopy.

Important potential complications to consider:

Re-bleeding upon deflation or loss of positioning

Discomfort/pain (patient should be given sedation and/or analgesia)

Aspiration (patient should be intubated and positioned with head of bed elevated)

Pressure injury (do not leave the tube inflated for more than 24-36hrs, deflate the gastric balloon within 12hrs, but reinflate if bleeding recurs)

Esophageal perforation (ensure the balloons are deflated during insertion and avoid overinflation of balloons in esophagus, confirm proper position)

Airway obstruction (if tube migrates)

Cardiac arrhythmias (check position, correct any electrolyte abnormalities, cardioversion if necessary)

Some helpful links with demonstration videos:

https://www.emrap.org/episode/placementofa1/placementofa

https://litfl.com/sengstaken-blakemore-and-minnesota-tubes/

https://www.aliem.com/trick-inflating-esophageal-balloon-blakemore-minnesota-tube-without-manometer/

References:

https://www.emrap.org/episode/placementofa1/placementofa

https://litfl.com/sengstaken-blakemore-and-minnesota-tubes/

https://www.aliem.com/trick-inflating-esophageal-balloon-blakemore-minnesota-tube-without-manometer/

Tsoris A, Marlar CA. Use Of The Child Pugh Score In Liver Disease. [Updated 2023 Mar 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542308/

Haq, Ihteshamul, and Dhiraj Tripathi. “Recent advances in the management of variceal bleeding.” Gastroenterology report vol. 5,2 (2017): 113-126. doi:10.1093/gastro/gox007

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sengstaken%E2%80%93Blakemore_tube

About the Author

Dr. Michael Simoes is a PGY-2 at at USF Emergency Medicine. He completed his M.D. at Florida Atlantic University Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine.